Homemade bone broth is a long‑simmered stock made by cooking animal bones with aromatics in water for many hours until the collagen and minerals from the bones dissolve into a rich, flavorful broth. Compared to regular stock, bone broth usually cooks much longer—often 12–24 hours for stovetop or slow cooker, or a couple of hours under pressure—resulting in a gelatin‑rich liquid that sets when chilled and can be sipped on its own or used as a base for soups, sauces, grains, and more.

What is homemade bone broth?

Bone broth is essentially an extended stock designed to extract as much flavor, collagen, and minerals as possible from bones. It can be made from chicken, beef, pork, turkey, or other animal bones, often with some cartilage‑rich parts like joints, knuckles, necks, or wings included. The bones are covered with water, sometimes after being blanched and/or roasted, and simmered gently with vegetables like onion, carrot, and celery plus herbs and spices for many hours.

Many recipes add a small splash of apple cider vinegar or another acid at the beginning to help draw minerals from the bones into the water, particularly calcium and magnesium. As the broth cooks, connective tissue and collagen break down into gelatin, which gives cooled bone broth a jiggly, jelly‑like texture that melts back into a silky liquid when heated. The resulting broth can be seasoned lightly for sipping or kept fairly neutral so it can be used across many recipes.

Equipment

- Large stockpot (at least 8–12 quarts) OR a 6–8 quart slow cooker OR an 8 quart pressure cooker/Instant Pot

- Large rimmed baking sheet for roasting bones (especially beef)

- Tongs for turning hot bones and transferring them from pan to pot

- Strainer or colander lined with cheesecloth or a fine mesh sieve for straining the finished broth

- Ladle for skimming foam during cooking and for portioning broth

- Heatproof containers or jars for storing broth in the fridge or freezer

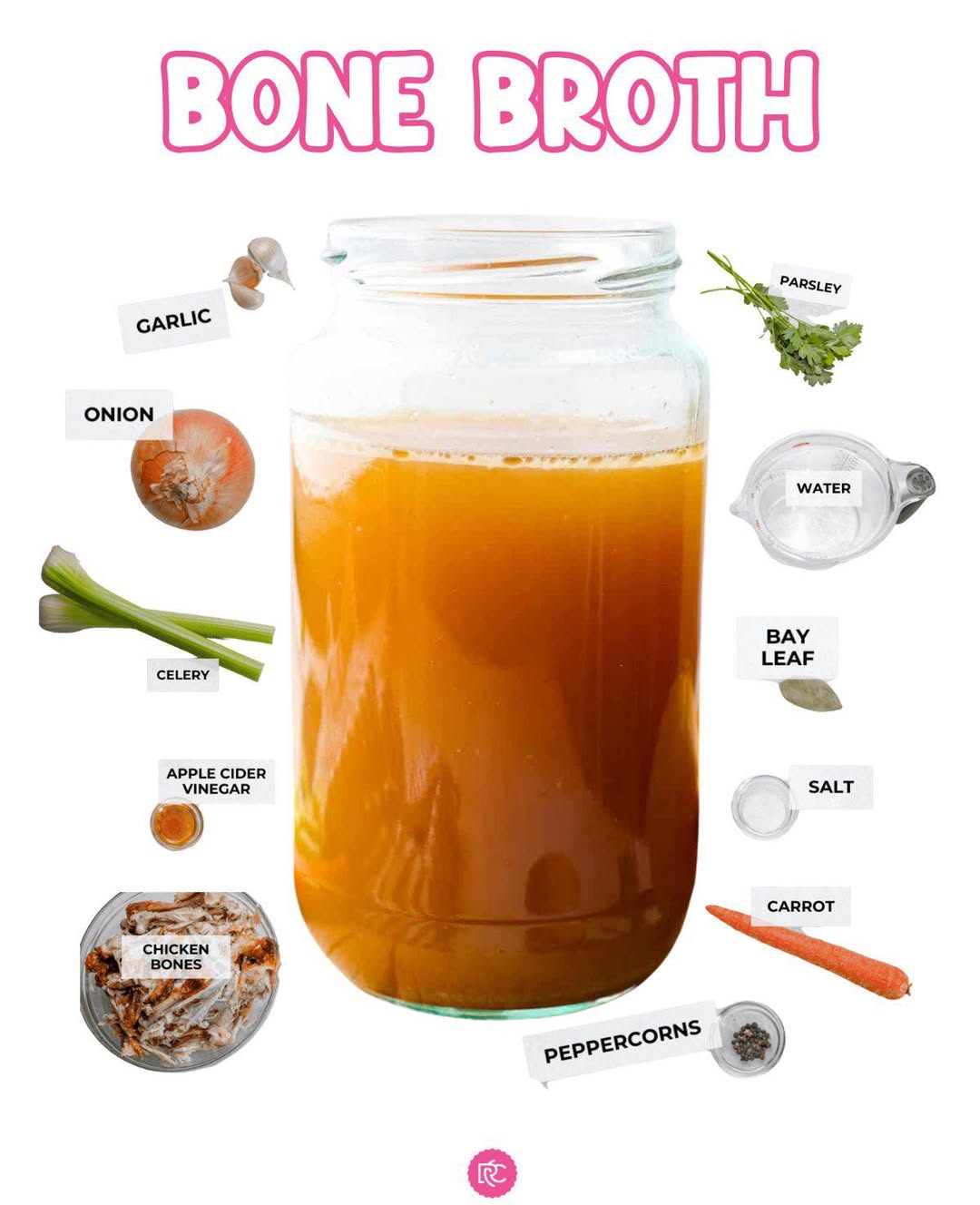

Ingredients

Ingredients for homemade bone broth are straightforward: bones, water, a splash of acid, aromatics, and optional herbs.

For chicken bone broth (slow cooker or stovetop):

- 2–4 pounds chicken bones and carcasses (from roasted chickens, backs, necks, wings, etc.)

- 1–2 carrots, roughly chopped

- 1–2 celery stalks, roughly chopped

- 1–2 onions, quartered (skins on for color are fine)

- 3–6 garlic cloves, smashed (optional but common)

- 1–2 tablespoons apple cider vinegar or lemon juice

- 2–3 bay leaves (optional)

- 8–12 whole peppercorns

- Cold water to cover bones by about an inch (usually 6–12 cups, depending on pot size)

- Salt, added lightly at the end if desired (many recipes keep broth unsalted for flexibility)

For beef bone broth:

- 3–7 pounds beef bones (marrow bones, knuckles, joints, oxtail, shank, soup bones)

- 2–4 carrots, chopped

- 2–4 celery stalks, chopped

- 2 onions, quartered

- 1 head of garlic, halved horizontally

- ¼ cup apple cider vinegar

- Bay leaves, peppercorns, and optional herbs like thyme or parsley stems

- 2–3 gallons cold water, enough to cover bones in a large pot or roaster

These ingredient lists are flexible; many home cooks treat bone broth as a “use what you have” recipe, throwing in vegetable scraps like onion ends, carrot peels, and celery tops instead of pristine produce.

Step-by-step instructions

Most bone broth methods—whether for chicken or beef, stovetop or slow cooker—follow the same broad pattern: optionally blanch and/or roast the bones, add them to a pot with aromatics, cover with water and vinegar, then simmer low and slow before straining and chilling.

For beef bone broth, recipes often start with roasting. Beef bones are arranged on a rimmed baking sheet and roasted at high heat, 425–450°F, for about 30–60 minutes, turning halfway, until they are deeply browned. Roasting caramelizes surface proteins and fat, adding deeper flavor and color to the broth.

Some cooks also blanch beef bones before roasting to remove impurities. Bones are covered with cold water in a pot, brought to a boil, and simmered 10–20 minutes, then drained and rinsed before roasting. This step helps produce a clearer broth by pulling out blood and scum that would otherwise rise to the top during the long simmer. Chicken bones, particularly from already roasted chickens, are usually not blanched but can be roasted briefly for extra flavor if desired.

Once the bones are prepared, they go into the cooking vessel. In a stockpot, slow cooker, or roaster, bones are placed in first, often with roasted vegetables like onion, carrot, and celery, plus raw aromatics like garlic, bay leaves, peppercorns, and any herbs. A tablespoon or two of apple cider vinegar is poured over the bones, and the pot is left to sit for 20–30 minutes before heating to start the mineral extraction process.

Cold water is then added to cover the bones by about an inch, leaving some headroom at the top of the pot in case of boiling. The pot is set over medium to medium‑high heat and brought just up to a boil, then the heat is immediately reduced to maintain a very gentle simmer—barely a bubble. A vigorous boil can emulsify fat into the broth and make it cloudy; recipes consistently recommend keeping the simmer low.

During the first hour or so of simmering, foam and scum may rise to the surface. A ladle or spoon is used to skim this off periodically for clearer broth and a cleaner flavor. After this initial period, the broth is mostly left alone, with occasional checks to ensure water levels haven’t dropped too far; if needed, a little more hot water can be added to keep bones just submerged.

Cooking times differ by method and type of bones. Many stovetop and slow cooker recipes simmer chicken bones for 8–24 hours and beef bones for 12–24 hours. Some sources note that even 6–8 hours can yield a flavorful broth, but a longer simmer gives more gelatin and deeper flavor. Slow cooker directions commonly suggest cooking on LOW for 12–24 hours, with 18–20 hours typical for a deeply flavored broth. Pressure cooker/Instant Pot methods shorten this dramatically: 2–3 hours at high pressure, followed by a natural pressure release, can produce broth comparable to 12–24 hours on the stovetop.

When the broth has simmered long enough, the heat is turned off and it’s allowed to cool slightly. The largest bones and vegetables are lifted out with tongs or a slotted spoon, then the broth is poured through a fine mesh sieve, or a colander lined with cheesecloth, into a clean pot or bowl. All solids—bones, spent vegetables, herbs—are discarded at this stage.

The strained broth is cooled more quickly by placing the container in an ice bath or dividing it into smaller containers. Once cool, it goes into the refrigerator overnight. On chilling, fat rises and solidifies on the surface; it can be scraped off and discarded or saved for cooking, depending on preference. The broth beneath, if rich in gelatin, will gel into a soft, jiggly mass that liquefies again when heated.

Salt is often added lightly at the end or left out entirely so that the broth can be adjusted to taste in the recipes it’s used in. The finished bone broth can be stored in the refrigerator for about 4–7 days or frozen for several months.

Texture and flavor tips

The hallmark of good bone broth is a rich, savory flavor and a high gelatin content that makes the broth wobble when chilled. Using bones with lots of connective tissue—joints, knuckles, feet, necks, wings—greatly boosts gelatin. For chicken broth, adding chicken feet, wings, or extra backs to carcasses is a common trick; for beef, including knucklebones and marrow bones helps.

Keeping the simmer low and steady prevents fat and impurities from emulsifying into the broth, which would make it cloudy and can affect flavor. Skimming foam during the first hour further improves clarity. Starting with cold water and bringing it up gradually, rather than pouring hot water over the bones, also helps coax more collagen and minerals out.

Apple cider vinegar is used sparingly: about 1–2 tablespoons per pot for chicken, up to ¼ cup for larger beef batches. Too much vinegar can make the broth sour, but a small amount, combined with a long cook time, helps extract minerals without making the flavor sharp. Many recipes also advise not oversalting early on; as the broth reduces slightly during long cooking, salt can intensify, so it’s safer to season lightly at the end.

Roasting beef bones (and sometimes chicken bones) adds depth and caramelization, producing a darker, more robust broth that works particularly well for sipping or for hearty soups and stews. For a lighter, cleaner flavor—especially for delicate soups—raw bones or lightly roasted bones work too.

Variations: chicken vs. beef, stovetop vs. slow cooker

Chicken bone broth is often lighter, quicker, and more versatile, making it ideal for everyday cooking. Using carcasses from roasted chickens plus extra wings or backs, a pot of chicken bone broth can be made overnight in a slow cooker or over a day on the stovetop. Chicken broth’s milder flavor pairs well with a wider range of soups (like chicken noodle, vegetable, or creamy blends) and grains.

Beef bone broth is richer and more intense, often used for sipping, for ramen‑style bowls, or as a base for French onion soup, beef stews, and gravies. It benefits particularly from roasting bones and from longer simmer times—12–24 hours—to extract maximum flavor from dense beef bones.

Stovetop, slow cooker, and pressure cooker methods each have advantages. Stovetop cooking gives the most control over simmer level but requires occasional monitoring and can be less practical for very long cooks. Slow cookers excel at “set it and forget it” bone broth, keeping a low, consistent heat for 12–24 hours with minimal supervision; they’re especially popular for overnight or 24‑hour beef broths. Pressure cookers dramatically shorten cooking time but still produce gelatin‑rich broth, making them a good option for busy schedules.

Make-ahead, storage, and ways to use bone broth

Bone broth is almost always made ahead; the long cooking time lends itself to large batches that can be portioned and stored. Once strained and chilled, broth can be kept in the refrigerator for about 4–7 days, with any hardened fat skimmed off before use if desired. For longer storage, bone broth freezes well in jars, plastic containers, or ice cube trays, where it can last several months.

Common uses include:

- Sipping hot bone broth with a pinch of salt and pepper or a squeeze of lemon as a warm drink.

- Making soups and stews, where bone broth adds more body and depth than boxed stock.

- Cooking grains like rice, quinoa, or barley in bone broth instead of water for extra flavor and nutrition.

- Deglazing pans for sauces and gravies, using broth instead of wine or water.

Because homemade bone broth can vary in concentration, many cooks dilute it with some water when using it in recipes, especially if it’s very gelatinous and flavorful. Tasting and adjusting seasoning as you cook helps keep dishes balanced.

As a recipe style, homemade bone broth offers a thrifty, low‑waste way to turn leftover bones and vegetable scraps into a deeply flavored kitchen staple. It relies on simple ingredients, slow, gentle cooking, and a bit of planning, but rewards that effort with a versatile, freezer‑friendly base that can elevate everyday soups, grains, and sauces far beyond what store‑bought stock can provide.